By Paul Koenig

posted with permission

My daughter, River, is having a hard time sleeping. Apparently, the pain of those new molars chewing their way toward the light is somewhat agonizing. Who knew? My own teeth have been around so long they're about ready to move on - only through constant applications of toothpaste and floss have I managed to convince them to stick around for one more pot roast. Really, though, most of the time I take my pointy little friends for granted.

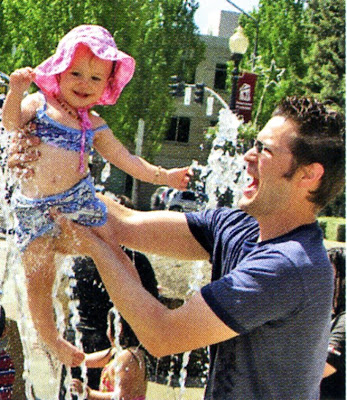

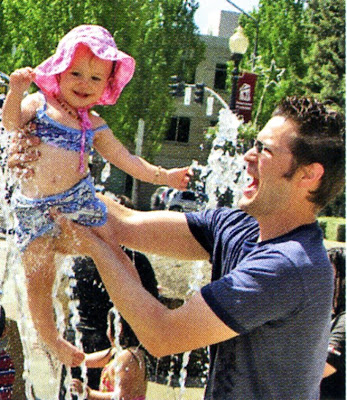

River does not. I'm impressed that she holds it together as well as she does, greeting each day with a delight and a frank curiosity that continue to charm those of us for whom eating dirt has long since lost its allure. She's the funniest person I know, and possibly the smartest, having learned all the different parts of the face, all the zoo animals and their sounds, and how to communicate in sign language despite having such tiny arms. All of this, and more, she accomplishes without benefit of tequila or opium, regardless of the pain in her jaw. Her only narcotic is regular applications of

mook (milk) from someone whose name is, I think, Mook, but who also looks like my wife, Erin.

Admittedly, the

mook is pretty important. As chief enabler, Erin continues to indulge River's now 18-month craving, and has no intention of stopping, a dedication that inspires admiration in some, abject horror in others. Being one of those modern, "involved" dads, I make dinner, clean the kitchen, and try to help out as best I can, though I often find myself removed to the periphery of River's universe due simply to the harsh reality of my inadequate, non-

mook-bearing man-teats.

Nighttime, in particular, is when River seems to need me least - asleep, I have even less to offer than usual. When bedtime arrives, when the toys are put away, the books read, the lights turned out - that is when the molars return to torment my daughter, and when she most needs my wife, her mother.

Which is why I was so surprised when, recently, after her bedtime

mooking failed to lull her to sleep, River began asking for

me.

"River's waiting for you," Erin called to me one night, somewhat bemused. "She's asking for her daddy."

This is a curious turn of events, I thought. I entered our bedroom, where River was sitting up in our bed.

"Daddy!" she said. "Hep!" (Help!) She held out her arms to me. Indulgently, I held her.

"Ooh-ooh! Ah-ah!" she said, making the sound of her favorite sleepy-time monkey. I procured the creature.

"Up! Up!"

I stood.

Then, wonder of wonders, she put her head on my shoulder and, with one arm around her monkey and the other around my neck, drifted off to sleep.

This, as it turns out, was to be our routine for an entire blessed month, an era that became known as The Time of Daddy-Hep. Or, from my wife's perspective, The Time of Mommy-Sleep. I took my duty seriously and did not complain, even when River would wake me after her 4 a.m.

mooking with loving smacks to the face, to demand, "Daddy, hep!"

"I'm sorry," Erin would apologize, sounding concerned. "I know you have to get up early."

"It's OK," I'd sigh long-sufferingly. "River needs her daddy."

And I'd pace to and fro, singing a lullaby, patting River gently on the back while she gently and amusingly patted mine, all the while suppressing tears of gratitude, which threatened to betray my true feelings about this wondrous new hardship.

It can be difficult being a modern father - one of those elusive, poorly drawn characters of whose role in contemporary family life no one is ever quite sure. What is

sure is that the old ways no longer serve; even if I had the time to recite the patent homilies of

Father Knows Best, I'm not sure I'd have the stomach.

We make our ways in the fashions that seem best to us, each man forging a brave new definition of

father out of bits of the past and pieces of the present. Just as the modern woman has made inroads into fields that were once the exclusive provinces of men, so has the modern man made advances of his own. Every time we hold our child, change a diaper, or wipe a runny nose, we realize our own power to nurture - while losing none of our "manliness" in the process.

Even so, in spite of it all, I can't deny the nagging feeling that I am not and never shall be a true "mother" - and, perhaps most shocking, don't want to be. It's not that I don't want to be needed. I want that more than anything. No, it's more that I recognize that there are limits to how much the line dividing gender roles can be smudged or erased - limits that are, for most, a practical necessity.

Defining exactly where that line is seems to be a kind of obsession with everyone these days, from the hellfire camps of the fundamentalists (clearly defined gender roles, and a pox on all ye who stray), to the we're-all-the-same notions of certain cultural postmodernists (limits? what limits?). In reality, it seems to me that The Line is a chimera, its shape and solidity up to each individual to define: What is true for you may not be true for me, and vice versa. Taking a hard line regarding The Line only makes it harder to perceive where it lies.

So my advice to all the other modern fathers out there who are searching for their just and rightful place in the modern family paradigm is this: Do not fear for the loss of your manliness. If "manliness" is a quality that could truly be lost, then you truly didn't want it in the first place. Better to strip away - gently, gently - all that is not real, all that is not true, and find the true core of manhood, which is perhaps far more nurturing and far less "manly" (by traditional definitions) than we might ever have imagined.

But I digress. As I was saying, all things evolve; change is the only constant. (I was saying that, if only to myself.) All too soon, the brief period of my daughter's need for me was over. One night I came to the bedroom, a spring in my step and a tune to hum, when I noticed that something was different. River was regarding me with something like suspicion; as I got closer, it only grew worse.

"Mommy!" she said.

I frowned. "No, Daddy!" I countered. She wasn't buying it. I picked her up.

She struggled. "Mommy!" she cried, a tone of panic creeping into her voice.

"But I've got your monkey," I offered plaintively.

I was thrown off my game. I tried all the usual stuff - patting, singing, pacing - to absolutely no avail. It was over. In seconds, my sweet, precious baby girl became a shrieking tangle of straining limbs, a crescendo of panicked cries of "Mommy!" issuing from her rather impressive vocal cords.

"ls there a snake on my head?" I asked Erin.

But no - at that point, a snake on my head would have probably been a positive development, something for River to focus on to take her mind off the hideous monster that was apparently trying to kidnap her and take her away from her mommy, perhaps for ever and ever.

The monster acquiesced. I returned River to her mommy.

I blame River's molars. In retrospect, I should have seen it coming. Although Erin had told me of their impending arrival, I just hadn't anticipated the impact. But

you try shoving a knobby piece of bone through your inflamed gum and see how it feels. You, too, would probably cry for your mommy. I doubt you'd even think of your daddy, unless he was standing in front of your mommy - and even then, you'd be thinking of him only as a potential threat to your immediate goal of getting to your mommy and her

mook.

So I don't get too wrought up about it. I know there will be times in the future when River will need her Daddy, too. Those times are made all the more precious because they are rare.

Paul Koenig is a freelance writer, musician, and artist currently residing in Arizona, with his wife, Erin, and their daughter, River.