newborn baby bruised/scratched by internal monitor

newborn baby bruised/scratched by internal monitorThe New England Journal of Medicine recently published a study that looked at labor (contraction) monitoring and different birth outcomes in hospitals. The study was conducted in the Netherlands (where rates of neonatal and maternal health and well-being are much better than in the United States). 734 women were assigned to internal monitoring (tocodynamometry) and 722 to external monitoring.

The purpose of the study was primarily to determine if there is a form of monitoring (internal or external) that leads to less unnecessary interventions, and therefore less fetal distress, better regulation of pitocin or other augmenting drugs, and less resulting c-section surgeries.

Continuous contraction monitoring is performed to (theoretically) monitor and artificially regulate contraction frequency, duration and magnitude. Because so many U.S. women today have their labors artificially started or augmented in some way via artificial oxytocin (pitocin), it has become necessary to monitor uterine contractions or face potential severe consequences to baby and/or mom such as uterine hyperstimulation and fetal hypoxia (lack of oxygen), which continues to take place anyway. [See video clip below for more on how this domino effect plays out.]

There had been speculation by some within obstetrics that internal monitoring (tocodynamometry) would lead to more effective 'feedback' and less intervention than the more commonly used external monitor (the belt).

Contraction and fetal monitoring is notorious for increasing unnecessary interventions and leading to cesarean section birth. It is hypothesized that this (along with the ubiquitously high use of pitocin and labor augmentation) in the United States is one reason we see our c-section rates souring while our neonatal and maternal morbidity and mortality rates worsen.

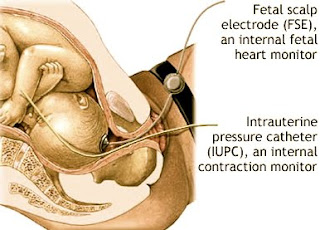

Typically, when an internal contraction monitor (tocodynamometry) is used, an internal fetal monitor is also placed (screwed into baby's scalp) or has already been in use prior to the tocodynamometry.

Typically, when an internal contraction monitor (tocodynamometry) is used, an internal fetal monitor is also placed (screwed into baby's scalp) or has already been in use prior to the tocodynamometry.-an intrauterine pressure catheter being inserted at some point during labor (whether or not this was the instrument used initially)

-analgesics

-antibiotics

-amount of pitocin given to the birthing mother

-increased time to delivery

-adverse neonatal health at birth.

Both internal and external monitoring end in distress to baby, hypoxia, and consequential c-section to the same rate.-analgesics

-antibiotics

-amount of pitocin given to the birthing mother

-increased time to delivery

-adverse neonatal health at birth.

Moral of the study?

Do not believe (or allow it) if you are told you need to have an internal monitor during labor to monitor your contractions OR the baby's heartbeat (internal fetal monitor). This monitoring, whether for contractions or fetal heartbeat, does nothing more than the external (belt) monitor, and in no way improves your likelihood of a safe and healthy birth experience, or your baby's outcome.

Internal monitoring does, however, increase your risk of placental or fetal vessel damage, infection, and anaphylactic reaction. Previous studies have demonstrated that as much as 38% of the time an internal monitor is used, it is misplaced during insertion (hitting the placenta, the baby, or being passed between the membranes and uterine wall). This occurs no matter the skill or experience of the practitioner doing the insertion. For all of these reasons, authors of this study have made the recommendation that internal monitoring not be performed.

Above: correct placement of an internal (contraction) monitor

Above: correct placement of an internal (contraction) monitor(in amniotic fluid next to baby)

Above & Below: incorrect placement of internal (contraction) monitor

Above & Below: incorrect placement of internal (contraction) monitor

BOTH forms of monitoring (internal and external) increase your chance of unnecessary interventions, the domino effect of hospital birth, distress to your baby, and the likelihood of having birth end in c-section.

Best thing? Ditch the monitoring altogether and find a birth attendant who believes in birth and is willing to do periodic (not continuous) checks on you and your baby.

If you'd like a gentle, normal, natural, peaceful birth that is as mother/baby-friendly as possible, the best thing to do may just be, as perinatologist, Dr. Marsden Wagner, so plainly put it - "get the hell out of the hospital!"

Related Reading:

Born in the USA

Pushed

Gentle Birth, Gentle Mothering

Gentle Birth Choices

Your Best Birth

The Thinking Woman's Guide to a Better Birth

Ina May's Guide to Childbirth

Related Videos:

Pregnant in America

Birth As We Know It

Orgasmic Birth

The Business of Being Born

Born in the U.S.A.

[End Note: I 100% agree with Rosemary Romberg when she states that it is utterly hypocritical to have a gentle birth (for mom and/or baby) only to cut up this newborn after s/he enters the world. Gentle birth does not end at baby's initial entrance into the world. This is only the beginning and the entire process -- being protected, cared for, loved, nursed, and mothered from the first second earthside -- matters a great deal! Genital cutting ('circumcision') has absolutely NO place in or around birth.]

Outcomes after Internal versus External Tocodynamometry for Monitoring Labor Jannet J.H. Bakker, M.Sc., Corine J.M. Verhoeven, M.Sc., Petra F. Janssen, M.D., Jan M. van Lith, M.D., Ph.D., Elisabeth D. van Oudgaarden, M.D., Kitty W.M. Bloemenkamp, M.D., Ph.D., Dimitri N.M. Papatsonis, M.D., Ph.D., Ben Willem J. Mol, M.D., Ph.D., and Joris A.M. van der Post, M.D., Ph.D.

ABSTRACT

Background: It has been hypothesized that internal tocodynamometry, as compared with external monitoring, may provide a more accurate assessment of contractions and thus improve the ability to adjust the dose of oxytocin effectively, resulting in fewer operative deliveries and less fetal distress. However, few data are available to test this hypothesis.

Methods: We performed a randomized, controlled trial in six hospitals in the Netherlands to compare internal tocodynamometry with external monitoring of uterine activity in women for whom induced or augmented labor was required. The primary outcome was the rate of operative deliveries, including both cesarean sections and instrumented vaginal deliveries. Secondary outcomes included the use of antibiotics during labor, time from randomization to delivery, and adverse neonatal outcomes (defined as any of the following: an Apgar score at 5 minutes of less than 7, umbilical-artery pH of less than 7.05, and neonatal hospital stay of longer than 48 hours).

Results: We randomly assigned 1456 women to either internal tocodynamometry (734) or external monitoring (722). The operative-delivery rate was 31.3% in the internal-tocodynamometry group and 29.6% in the external-monitoring group (relative risk with internal monitoring, 1.1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91 to 1.2). Secondary outcomes did not differ significantly between the two groups. The rate of adverse neonatal outcomes was 14.3% with internal monitoring and 15.0% with external monitoring (relative risk, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.2). No serious adverse events associated with use of the intrauterine pressure catheter were reported.

Conclusions: Internal tocodynamometry during induced or augmented labor, as compared with external monitoring, did not significantly reduce the rate of operative deliveries or of adverse neonatal outcomes. (Current Controlled Trials number, ISRCTN13667534 [controlled-trials.com] ; Netherlands Trial number, NTR285.)

Full Text at the New England Journal of Medicine